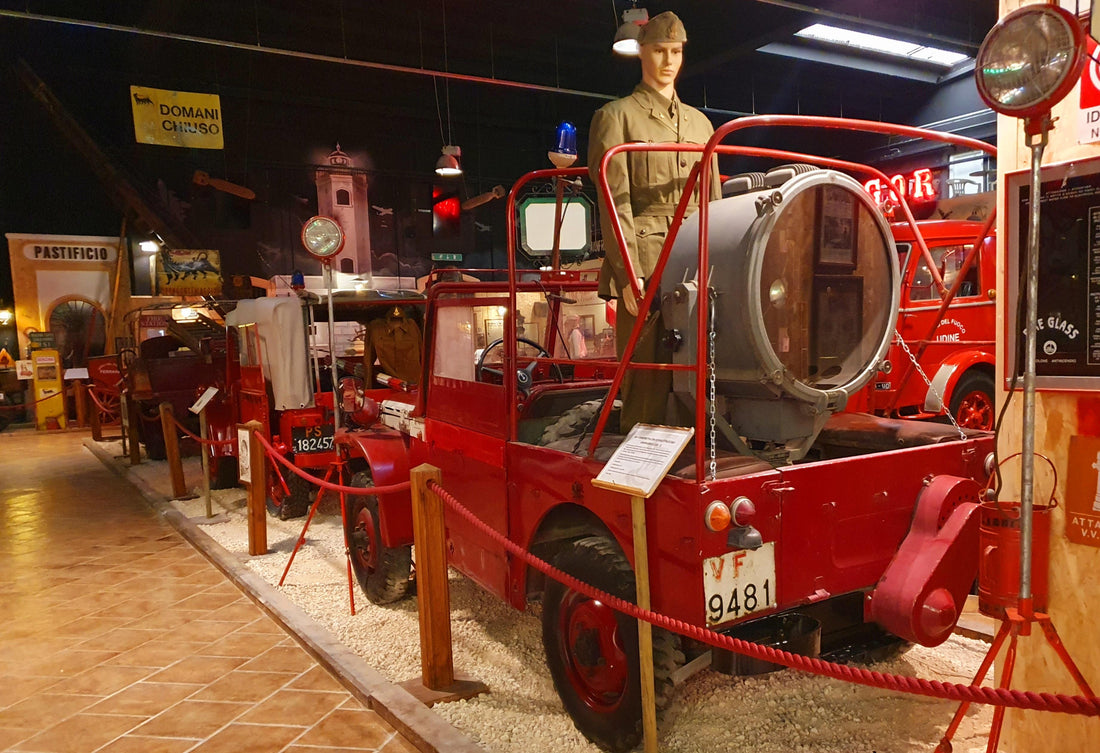

Alberto Angela's contribution to the Historical Museum of Firefighters and the Italian Red Cross in Manfredonia

Condividi

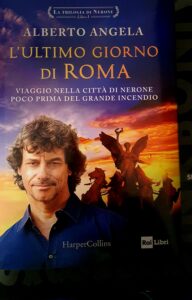

Few people know that Alberto Angela, paleontologist, science communicator, television host, journalist and Italian writer, in the early 1980s, still eighteen years old, discovered his first vocation and entered the Capannelle - Central Fire Fighting Schools of the Fire Brigade in Rome, to train and start working as a Firefighter. Passionate about this first job, in November 2020 he wrote and presented the first book of the Nero trilogy - The Last Day of Rome - Journey to the City of Nero shortly before the Great Fire . In this first book, he gives us a historical story with a cinematic style, incredibly engaging, one of a kind which, among other things, also managed to provide a notable contribution to the Historical Museum of Firefighters and the Italian Red Cross in Manfredonia, he gave us details on how the Roman Vigiles operated, how they were dressed and equipped on the night of the fire. During their rounds, the two firefighters on duty, the mighty veteran Vindex and the very young recruit Saturninus, were carrying out a job that was fundamental for the order and safety of the population of Rome, a city where fire was used for everything and tragedy was always lurking, and their daily work in that Rome largely made of wood with shops full of flammable goods overlooking the streets, was of vital importance. Based on archaeological data and ancient sources, and thanks to the contribution of historians and experts in meteorology and fire, Alberto Angela reconstructs for the first time in history, the very important episode that changed the geography of Rome and our history forever: the Great Fire of 64 AD. That night, the Vigiles (the word Vigiles included all the hard work of this profession, that is, patrolling and keeping watch (keeping vigil) on the streets of Rome during the night, the Vigiles were almost all very young, between teenagers and twenty-year-olds, the military imprint of the Vigiles Corps clearly emerged in their uniform and from the helmet that vaguely recalled that of the legionaries. The helmet was not made of bronze or steel, but of leather, because unlike metal it did not conduct the radiant heat of the fire. The tunic, since there was no uniform industrial production, was also different in color among them and varied between yellow and brown that shone yellow in the reflection of the flames. Each tunic was tightened at the waist by a belt leather (cingulum) with some thick leather fringes that fell between the thighs to protect the private parts. Almost everyone had axes (securis) on their belts, a double-headed tool very similar to the dolabra, with a sharp blade on one side and a point on the other, to be used as an axe or as a pickaxe to knock down walls, break down wooden doors, dig the earth, etc. Curious, however, were the buckets that were not made of metal, in fact most scholars believe that they were made of rush wood, covered in pitch to make them waterproof. In addition to these tools, essential for first aid in a fire, there were also weapons because having to monitor the streets at night, hunt down criminals or fugitive keys, they had to be armed and not having motorized vehicles and having to carry everything on their person for hours, all the fire-fighting equipment had to be essential, compact and light. Many of them carried long hemp ropes (funes) over their shoulders that wrapped around their torso like a snake. Just like the legionaries, in winter they also wore a cloak (sagum), which was inconceivable on that July night due to the summer heat. They wore what looked like military “amphibians” to protect their feet, a sort of soft leather boot (soccus) slipped like a sock inside a sturdy military sandal with a studded sole (caliga), a type of footwear, made up of two pieces, found incredibly intact on board the famous Roman wreck of Comacchio, and which must have been the classic amphibian of the legionaries, capable of protecting their feet from brambles, snow, cold and rain and it was not to be excluded that it was also an excellent solution for resisting fire. This reconstruction of the Vigiles uniform is unfortunately hypothetical, because no contemporary author has ever described it in detail, but judging by the numerous ancient and modern sources, it seems plausible. The number of Vigiles on patrol that night is also hypothetical. However, since the night was a risky shift during which the Vigiles also performed police duties, with the obligation to quell brawls and arrest criminals and thieves, a relatively small number consisting of eight men, i.e. the basic unit of the legion (the famous contubernium, i.e. men who shared the same tent and the same line during marches), seems a reasonable hypothesis.

This is a summary of the exciting story of the Roman firefighters who fought for nine days (other scholars speak of seven days and seven nights) to put out the flames that, from Saturday 18 to Sunday 26 July 64 AD, destroyed Rome causing the complete loss of three districts while seven others were damaged, causing thousands of deaths and 200,000 homeless survivors.

This is a summary of the exciting story of the Roman firefighters who fought for nine days (other scholars speak of seven days and seven nights) to put out the flames that, from Saturday 18 to Sunday 26 July 64 AD, destroyed Rome causing the complete loss of three districts while seven others were damaged, causing thousands of deaths and 200,000 homeless survivors.

With these precious indications provided by Alberto Angela, in the Historical Museum of the Firefighters and the Italian Red Cross the hypothetical history of the fire of Rome has been improved, the uniform worn in those unfortunate days of Rome and the operating methods of the two Vigiles Vindex and Saturninus that students of all levels and all visitors will be able to admire in the Museum.